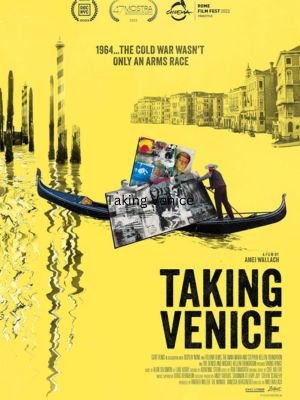

The 1964 Venice Biennale was a global art exhibition in which Robert Rauschenberg received the prestigious Golden Lion. “Taking Venice” is a documentary about the strategies that led to Rauschenberg’s triumph. In her film Amei Wallach, an art critic and creator of fine art documentaries (she has done “Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: Enter Here” and “Louise Bourgeois: The Mistress and the Tangerine”) portrays Rauschenberg’s win as some sort of American power celebration after World War II.

A team of quick-witted US diplomats and players in the world of art contrived a victory for Rauschenberg, whose work involved combinations of collage, painting, silkscreen, and occasionally everyday household objects, curiosities or junk. This was pop-art epoch when many exhibitions especially in the United States made visitors ask questions like – Is this really Art? And just like Jasper Johns; Roy Lichtenstein; Claes Oldenberg; Andy Warhol he became one of its examples. Before Taking Venice he had been condemned by everybody at home and abroad as what he called himself: “a clown”, or “a novelty”. But his popularity was increasing with each day, sales were skyrocketing so it would be wrong not to compare him to Philip Glass who took a taxi during premier of his “Einstein on the Beach” opera at Metropolitan Opera theatre. There’s something uncanny about how certain cultural figures keep ascending throughout their careers, which Rauschenberg had. He seemed like someone who was going to get there anyway but needed help getting over the top.

In this respect, Taking Venice was ripe for American government exploitation at that year’s Biennale. The US had become a superpower with President Kennedy being depicted prominently in many works by Rauschenberg before his assassination six months prior to Biennale. None of his predecessors in the position had ever shown such deep love for art. During his tenure, the State Department under Kennedy sought to prove that America produced unique, courageous grand arts which were not only beautiful but also meaningful and could explain why one might want to be on Team American rather than on Team Soviet Union apart from being dumped into overseas markets like blue jeans and Coca-Cola.

It was a matter of making it as a journalist right before the arrival of Wallace who spoke with people in their seventies and eighties that were lucid at that time, as well as some witnesses of the 1964 Venice Biennale. The most important person she got was Alice Denney who had been an assistant commissioner at the US pavilion and was instrumental in this little chapter of art history. Her husband worked as deputy director in charge of intelligence at the State Department’s Bureau. She proposed Alan R. Solomon be appointed US Biennale commissioner together with her. Solomon was a sleek clever man who according to New Yorker writer Calvin Tomkins “had finesse when he fought.”

What is more, Solomon was a genius in his own way, always recognizing that any unwritten law isn’t really a law at all and which can still be bent or broken if the move is so smart that it makes people feel amazed or jealous for not having come up with it first – and when its beneficiary seems to be a winner by all means. Rauschenberg did seem like a winner. He became an entertainer, provocateur and what we know as brand today besides being gradually gaining significance as gallery art. The collective efforts put together by Rauschenberg’s can-do-attitude and Solomon’s alliance created an unstoppable momentum.

As written in the New York Times obituary for Solomon: “Insisting on eight sizable one-man shows for artists, [Solomon] soon ran out of space in the cramped American pavilion at the public gardens,” where all official exhibits were located, each artist allowed only one painting. “Thus, with the tacit consent of negligent Biennale officials, he stretched his exhibition into an empty American consulate building to the chagrin of other countries’ delegations deprived of such preferential treatment.” Some improvisation also took place then. During nighttime builders constructed a temporary rooftop over an outdoor esplanade next to the official site (today we would probably call it “pop-up exhibit”) where Rauschenberg’s works could be moved from an auxiliary site to mitigate dissatisfaction about them being displayed elsewhere than at the official show place of exhibitions. They gave prominence to Rauschenberg rather than any other artist—this was their strategy at Biennale.

This story is fascinating . However , this has resulted in counterproductive styles . By doing this , however , “Taking Venice” commits the sin of being a normal film , which means that it becomes boring , ordinary , and commercial . Motion graphics , re-creations , digital additions and erasures into historical photographs are cluttering up scenes and montages that would have been far more affecting if we could regard the images just as they are . There is also a hyped-up score ranging from Steven Soderbergh heist flick to Michael Bay action thriller . This is not conveyed for many reasons including the fact that Rauschenberg’s pop sensibility comes across cinematically. One of them is the newness of Rauschenberg’s style circa 1964 which feel very obvious in today’s overused modern non-fiction filmmaking techniques.

“Taking Venice” also flashes back to move around time in order to explore Rauschenberg’s evolution as an artist and human being. In addition, there are digressions about different topics such as Rauschenberg’s love affair with Jasper Johns or his “experiments and collaborations” at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where he had worked with other well-known figures such as composer John Cage, and choreographer Merce Cunningham (the latter arrived in Venice at last, held a performance on the eve of awards consideration which turned out be the most talked-about event among all others). These breaks draw attention from what American government was doing to tilt the exhibition towards Rauschenberg. Though it is compact in terms of running time, it seems so crammed and jumbled that you sometimes get a feeling that this movie was almost going to turn into a simple critical-biographical documentary about Rauschenberg but then refrained from doing so.

So, what is it? Denney tells the film people, “May be we would have won it anyway but we really contrived it”. Later on, Rauschenberg himself expressed doubt about the political motivation that elevated him to the top. The fact that his triumph had been accomplished through a government-sponsored PR campaign as opposed to being natural might go against the American myth of a bright and shiny new America defeating ossified European gatekeepers in a contest purely based on merit. The movie does not explore this irony deeply enough. After the war ended, US became an insatiable economic and industrial colossus; labeled by some critics overseas (and at home) as cultural and economic colonizer—though US viewed itself as one of great liberators. Rauschenberg’s victory only magnified such grievances. However this presentation shows Venice operation as Yankee chutzpah which worked for USA and Rauschenberg: a process movie.

Also, Read On Fmovies