“Kidnapped” is so core-shaking in its primality that it would seem unwatchable. However, it proves intoxicating at times, almost overwhelming and a triumph of casting, an economical, impassioned screenplay and the guidance of 84 year old’s cowriter-director Marco Bellocchio; Who could arguably be one of the greatest living narrative filmmakers not widely acknowledged as such.

Edgardo Mortara is a Jewish baby boy who was baptized by his family’s nanny (a Catholic teenager) on impulse in Bologna, Italy. The latter event becomes known to him six years hence when his father Salomone Momolo informs Father Pier Gaetano Feletti about it. Consequently, the child is taken away under police orders authorized by Feletti who states that no Christian can be raised by parents from another faith. It is explained to the Mortaras’ that the boy can only remain with them if they all convert to Christianity (even their other children). Salomone “Momolo” Mortara (Fausto Russo Alesi) and Marianna Mortara (Barbara Ronchi), Edgardo’s father and mother respectively choose a third way: to give him up in exchange for their household religious identity while using legal means and newspapers as their weapons in fighting church and state hoping for Edgardo’s release back to his birth family or some form of disestablishment.

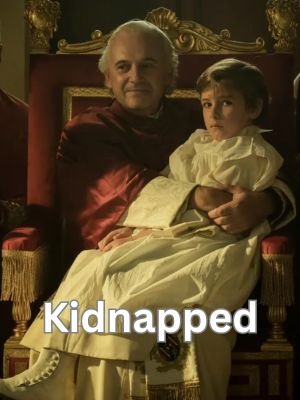

A task impossible-seeming? Parents don’t have time on their side. Over sixteen years the film takes place. We know already that justice grinds slow or hardly moves at all but also that human beings are complicated psychologically organisms who do not always behave as hoped for or expected because they can change. Edgardo grows up while his family visits Pope Pius IX (Paolo Pierobon) periodically; he comes into new surroundings and adapts to them (Edgardo is portrayed by Enea Sala as a child and Leonardo Maltese as a young man). After an early period of emotional chaos in which Edgardo alternates dutiful attempts to adjust to his new life and impulsive acts of rebellion/rejection (there’s also an attempt to steal him back) he does eventually become a Catholic, and a devout one at that. (A pair of rhyming images shows little Edgardo hiding under his mother’s skirts to escape the police early in the story, then later hiding under a priest’s frock coat during a game of hide-and-seek.)

Hardly anything can be more basic among all possible scenarios than forcibly removing children from their parents. “Kidnapped” develops that sense of violation further even while returning repeatedly to the family’s quest for justice. The film also raises philosophical questions related to these fundamentals without making them too abstract: What do you do when someone kidnapped doesn’t want to be rescued? Is it still kidnapping if you take them away from such adaptive conditions against their will?

In addition, “Kidnapped” is an insightful scrutiny on power acquisition, retention and use as well as the negative reactions of those who have known what it means to be in power when they wake up one day and realize that at least a part of it is going away. Although there are many films about powerful organizations destroying individual families while the families try to repair them and fight back, very few recent ones explain the dynamics of oppression and resistance so directly and without any reference to religion like “Kidnapped.” The fact that these oppressors are for the most part mild-spoken rather than openly wicked bothers us more than anything else that happens here. Sometimes their behavior suggests that they feel ashamed doing what they are doing enforcing regulations made by their own organization. There exist some rules and laws you know? They must be followed; no offence taken because it’s not personal.

Not until a representative from Jewish newspaper in Bologna met with Pope did anything change: quality, tone or manner of visitors’ speeches even surpassed their substance in importance.“Recall your place, kneel down; how can you forget yourself here?” mentions Pontiff. Furthermore he adds,“I could cause you great pain; I could force you down again into your hole from where we came.You remember when ghetto gate was closed every night; don’t tell me you forgot?” When any officials from (secular) legal system challenge Feletti even slightly back he gets angry. “I want to clarify this point regarding Church decisions which have been declared by his court,” says he to judges coming for questioning him.

Therefore, the church in the 19th century appears as a corrupt institution that was drunk with power and whose objective was to act as middleman between God and humans thereby eliminating other religions through male supremacy guilt-tripping almost all subjects into donating money towards church projects as well as listening to what it says besides stealing wealth or land. (Towards the end, it becomes clear that Papal States are going to be hit by secular government hence the top echelons of Church start deciding on where to hide all their loot.)

Nevertheless, none of these characters wearing vestments act like a typical villain. They may mostly be seen as bureaucrats with turned-around collars: company men. At times Pope Pius IX looks like he might develop into the one really hiss-able exception. But the way Pierobon does him (with an air of childishness and self-disgust that reminds one of late Ian Holm) suggests that he’s not only warped from life among the super powerful, but also has some sort of unidentifiable mental problem which will never receive proper attention.

This material does not appear as a coolly observed case study with bare facts laid out, but more like a grand and tragic opera or an old time epic movie melodrama that would have been either shot in burnished black-and-white or feverish Technicolor depending on the decade. It’s almost as if Francesco Di Giacomo’s cinematography was inspired by Old Masters like Rembrandt. A touch of Gordon Willis’ work in the “Godfather” trilogy lingers in the form of single-source lighting falling on apparel and faces. Fabio Massimo Capogrosso’s riotous, noisy orchestral score helps to weave together a script that could otherwise seem too cold or schematic. It never lets you forget whose side it is on, (the side that says “kidnapping, bullying and oppression are bad”) even when “Kidnapped” is endowing its most perverse characters with depth—and reminding you that while major characters may sometimes be shaved down to little more than their plot functions for expedience (the film lasts over two hours), they remain fully human.

“Kidnapped” might turn out to be one of those films similar to the older classics it obviously models itself after where if you sat in the dark with a stopwatch and timed them they’d only occupy a few minutes of screen time. I just wish this wasn’t portrayed off screen because it makes some parts confusing especially when these confusions are not always clarified (although withholding details of an early baptism until near the end courtroom scene proves to be brilliant; it gives every bit of story more tragedy –and at the same time silliness).

It has been a wonderful year for cinema so far and another important film is “Kidnapped,” which tells its story through immediacy and anger while also being influenced by past greats from decades ago or even centuries gone by.

Also, Read On Fmovies