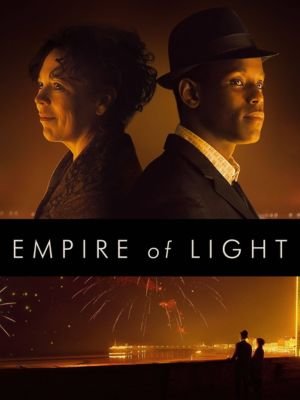

To commemorate his grandfather who was a former World War I soldier, Sam Mendes’ previous movie was 1917, a one-shot epic war film. But, Empire Of Light, his new film is an understated 80s drama set amid an antiquated coastal town movie theatre; it’s a complete departure in every sense of the word. Still there is also a personal angle to this story-telling – Mendes has talked about it as being in memory of his mother who lived with mental illness. This results in a period melodrama that earnestly tries to be many things at once, some more successful than others: mismatched love affair, nervous breakdown portrait and snapshot of Thatcher’s racially charged Britain and kind of love letter to cinema.

By the time we meet her (Olivia Colman), she has become another disenchanted employee of the movie house having an unsexy extramarital relationship with its manager (played by Colin Firth as some sort of an anti Darcy). Hilary’s past psychiatric issues are slowly revealed indicating her numbness due to continuous use of antidepressants. Again Colman gives yet another outstanding bone shaking performance even if occasionally Hilary’s story succumbs to melodrama at its most lazy; sometimes you can feel that buttons are being pressed.

And then Stephen comes by injecting some brightness into Hilary’s dull life. At times he assumes the role of manic pixie dream boy—he brings up bringing back to health a pigeon which is as subtlest metaphor like getting hit directly on your face—and also clumsily inserted so as to teach Racism 101 for clueless white characters but he is played captivatingly by Ward. For future leading-man roles this stands out as an impressive calling-card.

While Hilary’s health takes over, any hint given by the title (and marketing) towards Cinema Paradiso-like elegy starts disappearing. Almost all through the movie theater seems like less important character, a peripheral aspect reduced into mere window dressings. Characters in this cinematic love letter seem to show little interest in the movies being shown; only Toby Jones as the projectionist occasionally sways towards cinephilia.

But what window-dressing! Mendes brings forth a highly specific, instantly recognizable British experience of economic pessimism, chintzy curtains and free NHS glasses through Roger Deakins’ usual skilled cinematography and Mark Tildesley’s period-accurate production design. The filmmakers find beauty in this ugliness especially the epic grandeur of the cinema itself: two screens are shut down, seemingly condemned, with Hilary and Stephen conducting their secret affair in an empty ballroom that seems like some lost archaeological gem. After the pandemic it instills a sense of how inherently fragile going to the movies actually is.

At its best it is genuinely evocative, and although (this being his first solo screenwriting credit) Mendes’ script does not always work there are moments when he lets Trent Reznor/Atticus Ross’ fragile brooding score —and/or just let his camera—do most of the talking. As a whole it does not quite gel but you can feel enough trueheartedness about it to know that this comes from deep within.

Also, Read On Fmovies