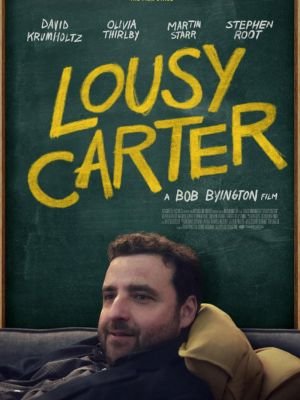

Austin-based filmmaker Bob Byington never takes an easy route, especially when working with the same tired middle-aged sadsacks that have populated every indie dramedy under the sun. They’re mumblecore movies, but not really because they’re too deliberate and snaky for a genre that implies “deliberate” or “snaky”; he dares you to stare into the abyss of tedium surrounding his characters’ often-ugly-souls. That’s certainly true with his latest, short but far from breezy “Lousy Carter,” which asks: What if a man’s terminal diagnosis just makes him more of a loser?

The loser in question is “Lousy” Carter (David Krumholtz), a schlubby. Self-centered literature professor who suffers from gifted-kid syndrome in the most acute way possible. He was praise for being talented as a child artistically and it only stopped him from growing up. That and also having an artist mother (Mona Lee Fultz) who is disapproving and critical of everything and whose instability drove his sister (Trieste Kelly Dunn) away from their relationship and should have made him smarter about brains that aren’t his own.

Instead, he spends his days snapping at those few students who deign to hear him blather on about F. Scott Fitzgerald and Nabokov while sleeping with his Russian lit colleague’s wife (Jocelyn DeBoer). Always wears a blazer over T-shirt over baggy jeans; sometimes swaps out blazer for hoodie.

But when another disaffected physician puts a terminal diagnosis on Lousy’s head along with six months to live, Lousy does nothing — opposite of what most protagonists would do when abruptly confronted with mortality like this. This is where “Lousy Carter” gets funny and deadpan in its own uninteresting ways. As Byington & Krumholtz take great joy in zagging where most movies about realizing you’re gonna die soon zag.

It’s “Ikiru” flipped on its head, instead of a man finding out he’s dying and deciding to turn his life around. Lousy sees it as an excuse to dig even deeper into his vices — all without telling anyone or really doing anything differently at all. Save for fucking his best friend’s wife more often. Or aiming his gaze lower at the young lit student (Luxy Banner’s sardonic. Lone Star-swigging Gail) who pays him some mind. She seems less interested than she is bemused — a kind of anti-Lolita who sees him as a pitiable experiment; how much trouble can I get this miserable person in?

This high-wire act is held up by Krumholtz’ slumping shoulders; “Lousy Carter” is a perfect follow-up to his Oppenheimer performance (where he plays ol’ Oppy’s Jiminy Cricket), caustic enough for two. There are no such moral compunctions here. As Krumholtz shuffles through scenes (courtesy of Byington’s disorienting. Nearly dreamlike editing) with the blank resignation of an inmate who just wants it over with already. It’s wonderful work that speaks volumes even while plumbing the depths of Lousy’s emotional intelligence. “You’ve diminished over the years,” Starr tells him flatly, “You’re a version [of yourself].” He isn’t wrong;

To be sure, such ambitious swings make “Lousy Carter” hard to swallow sometimes, even in its breezy 80-minute runtime. The homespun, DIY indie aesthetic suits Lousy’s lack of ambition well enough but creates some visual gags that just don’t land — the handheld vibe can’t capture them. (The twee, tweedy chill-hop score by leafcuts consistently sounds like waiting for a YouTube video essay to finish.) We see the world through Lousy’s two-dimensional understanding of it. Which tends to flatten everyone else out too. That’s right: Lousy hardly cares about them at all. Do we?

At its best, “Lousy Carter” feels like a mean joke on the character himself — the type of person who is so convince he is a genius that he doesn’t want to ruin it by actually doing anything. This is Krumholtz’s moment; he hits levels of sardonic despair not see since Paul Giamatti in “American Splendor.”

It takes bravery to play someone so unlikable and disinterested that a medical death sentence feels like gentle release. Like the authors he loves. Lousy is a “museum piece,” something interesting because of what it represents but useless for those around it. The film’s most courageous move may be Byington’s nod of agreement with this fact.

Also, Read On Fmovies