“In my whole existence, African people were just slaves,” Malik (Jordan Bolger) declares at one point in The Woman King. A Portuguese-African man born to a mother thieved from her nation of origin; he’s in Dahomey (modern-day Benin) during a quiet moment thinking about the mass displacement of slavery — the only place she was free — a connection with roots that many could never make. It is this Africa that Gina Prince-Bythewood’s fifth film wants to find: the multi-faceted one obscured by years of being known only through stories that represent it as nothing but a traumatised continent, rather than one with its own kingdoms and complications. The American filmmaker presents Dahomey as a kingdom of colours, particularly in the opulence of the king’s court. But while finding this African decadence, it never forgets that imperialist wealth comes at a moral cost – one which the movie spends itself trying to calculate. It grapples with its admiration for an affluent kingdom and a warrior class led by women – as well as the uglier facts about how such wealth is made.

Braveheart and The Last Of The Mohicans are among historical epics summoned by Prince-Bythewood when depicting Dahomey’s all-woman kingsguard, the Agojie (also referred to as the Dahomey Amazons or “the bloodiest bitches in Africa”, according to one Portuguese slaver), and their struggle against their larger Yoruba neighbours to regain independence from Oyo Empire. Her romanticism shares DNA with those films, still interested in intimacy even as her scale expands: her last film, The Old Guard, spun romance over millennia; love stories – platonic, familial and romantic – are here drawn across ethnic and national faultlines.

Those stories act as counterweights to some brutal action. The choreography is thrillingly brawny and efficient, set-pieces mounted with lean ferocity. But The Woman King does not only reserve spectacle for fights, depicting the community’s ceremonial songs and dances with thrilling verve. The craft here is beautiful – the make-up and costume design lush and detailed; they draw attention to the physiques of the warrior women, their shoulders and backs celebrating martial prowess as much as beauty.

The movie has a lot on its mind. There are lyrical sequences involving music and movement. European slavers are also beaten to death with their own chains at some point. To its credit, it largely holds off presenting Dahomey uncritically as the one good empire: structural imbalance and patriarchy still reign inside its walls. Dana Stevens’ screenplay wrestles with the kingdom’s complicity in selling slaves to Europe and America whom they trade for wealth, luxuries, weapons and military power; this carries through into some satisfyingly revisionist wish-fulfilment where John Boyega’s King Ghezo and his Agojie realise evil of slavery, combat it along with colonial manipulation toward Pan-African unity. Oyo come to represent their opposite: evil of collaborating with slave trade; myopic route to power that Dahomey should fight against.

There are a few stumbles. Some characters’ arcs follow predictable paths in script which also slows somewhere around midpoint before rushing to finish line during third act. Terence Blanchard’s score threatens to swamp quieter moments with overwrought schmaltz too (shame given composer’s usual grip on drama).

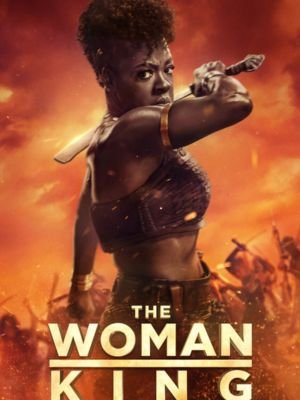

Luckily, emotional genuineness from the actors keeps these moments afloat. Viola Davis as steely-eyed leader Nanisca best demonstrates this when she shoots someone down with a single look (why should we be surprised?). But it’s what her performance doesn’t do that makes it so quietly devastating. Atim and Mbedu, who were both standouts in Barry Jenkins’ The Underground Railroad adaptation earlier this year, ground the film even as it hits more melodramatic beats. Mbedu (who co-leads here with Davis) is magnetic in the same way she was in that series; while Atim feels like the most natural presence on screen, full of lived-in-ness but still hauntingly memorable at the film’s margins. Lynch is a delight, funny and sly and brimming with earned confidence; and Boyega is equally compelling — just watch his eyes flicker between youthful indecision and royal authority as King Ghezo. Each actor, needless to say, has room to build out rich interior lives.

It’s a good thing they’re all so impressive: When this cast comes alive in battle — which they do often, with such physicality and sheer joy — Woman King can hit like very little else.

Also, Read On Fmovies