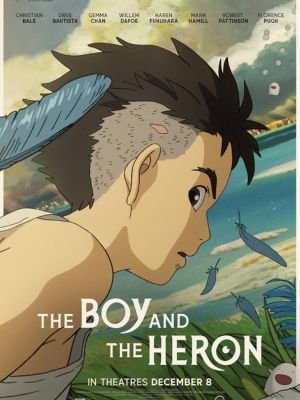

It made sense when Hayao Miyazaki announced his retirement after The Wind Rises in 2013. Animation takes a long time, The Studio Ghibil co-founder was no longer getting any younger, and an innovative film about the life of Jiro Horikoshi as the last movie could have been seen as a fitting end to Miyazaki’s career of all his previous works. This film is a personal biography with which the filmmaker shares his opinion regarding art.Thus, it was exciting when news broke that Miyazaki had come out of retirement yet again but it meant more pressure for this new project. Is The Boy and the Heron a better ending for a legendary animator’s career than The Wind Rises? And does it offer something fresh from him?

On this first account, it depends on what your expectations are for (until he changes his mind) Miyazaki’s last movie. The Boy and the Heron feel like a sort of return to its original form, having too much in common with earlier films directed by Miyazaki himself both stylistically and thematically – sometimes just like My Neighbor Totoro – where he has told us about an escape into fantasy world by kids who don’t want to face some hard realities.

Nevertheless, there is nothing repetitive in this story; even so, we cannot say that he is imitating himself without using it efficiently. Therefore, “The Boy and the Heron” brings to viewers’ minds images recalling either Spirited Away or Totoro: the first thing you will pay attention to while watching are countless magical creatures or small lovely things that can only be seen in dreams at night; therefore these cartoons possess much more advantages over their ancestors because during those years their director has learned enough lessons from life his work now is full of humor and magic, perhaps this explains why adults enjoy most anime movies.

However despite its playful appearance, “The Boy and the Heron” is a symbolic expression of reality that acknowledges human perception; even though this cinematic work may seem incredibly funny and light-hearted with its world of fantasy, it is still full of meaning as far as children’s lives are concerned. For example, one frame in which a guy pretends to be sick so as to skip classes illustrates his decision in vivid detail.

At least, The Boy and the Heron looks like Miyazaki’s most beautiful work ever. I mean, who would not have been captivated by those settings and imaginary worlds presented here – especially when we recall such a scene from his movie where a young boy runs through Tokyo streets during some raging fire that turns people in the background into silhouettes fading away? Ghibli films have always been visually stunning (mostly), but this one feels like an epitaph for all animation: apart from certain breaks without any speech at all with characters moving slowly in silence showing “ma” (that would be void or emptiness) makes Disney Studios and American cartoons look cheap before their fans while it also remains absolutely unique and emotionally touching till the end.

The Boy and the Heron does deliver on its promise of being Miyazaki’s swan song. A film for kids, which is also a farewell from an old man who contemplates his own death and legacy as well as the world that would be left for those coming after him; this was made by Miyazaki to prepare his grandson for the eventual departure of his grandfather. As such, its original Japanese title – ‘How Do You Live?’ is more pertinent to the themes of grief and loss in than ‘How Do You Live (On, After Losing a Loved One)’ given as its English name. This film has been more emotionally raw than any other work by Miyazaki, with longtime Ghibli composer Joe Hisaishi rising to the challenge and delivering a score that is both melancholic and playful throughout – like what one might hear if Up were continued past its opening ten minutes.

What makes The Boy and the Heron so quintessentially Hayao Miyazaki is how much of himself there is inside it – more even than in The Wind Rises. Like Miyazaki at that age, our main character hates everything around him, evident in earlier works like Princess Mononoke or Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. Furthermore, some aspects of her son’s life parallel those found between mother characters in her films and Hayao’s father who used to make airplane components during World War II. This war plays out not only through large-scale battles but also through little things such as missing items like tobacco products.

Thus The Boy and the Heron may be said to be a last testament from a great storyteller about his career making richly rewarding yet accessible movies while looking back at what he has left behind for his grandchild; an elder statesman’s final message to young people telling them never to take fantasy seriously enough. The movie argues that even if the world is getting worse by the day, and you are angry about it, The Boy and the Heron still exhorts one to face the truth – a surprising thematic parallel with Miyazaki’s fellow animator who directed his final Evangelion film.

In that sense, this may be considered as Miyazaki’s last film. My Hero Academia has similar ideas, “Next, it’s your turn.” This is more like a cautionary statement or dares to other people who might wish to follow in his footsteps when creating their own works, but on the other hand, it feels like an admonition for those of the next generation to become better than their predecessors.

Conclusion

The Boy and the Heron is Hayao Miyazaki looking back at years where he created whimsical stories set in fantastic worlds. It is Studio Ghibli’s most visually complicated movie so far while reflecting on what was left for our planet by one of its greatest directors. A fitting close from Miyazaki and a perfect end to his career.

Also, Read On Fmovies