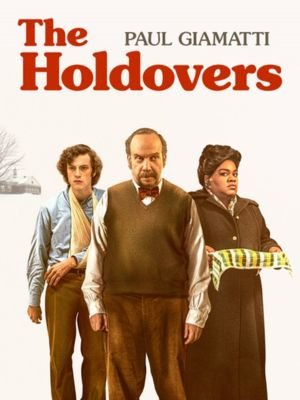

Alexander Payne has been making tepid dramas for around 20 years now, but his latest – set in a snooty New England boarding school in the year of our Lord 1970 – plays as an instant coming-of-age classic. The animus and eventual friendship between the unlikely duo of a surly history teacher (played by Paul Giamatti) and his angry pupil Angus Tully (Dominic Sessa in his debut movie) is the focus of The Holdovers, it tells us about their forced proximity during Christmas holidays.

Payne mentions director Hal Ashby as one influence among others, he states that he tried to make films that were not only like those made in the 1970s but also like Ashby’s Harold and Maude and The Last Detail, which can be seen through retro-stylized studio logos on The Holdovers. On closer inspection, however, it seems more akin to the work of John Hughes throughout much of its run-time. At first glance, some aspects of this plot may appear clichéd these days but it is one film that takes time to un-peel its chief characters layer after layer resulting into a meaningful drama with a lot of character–centered comedy or sometimes both at once.

Wes Anderson’s Rushmore-like notion of Barton Academy can be traced through how Payne presents this prestigious Christian prep school. It also looks like both a setting from another time and a place dropped from nowhere into no other place than Payne’s mind (which probably borrowed from various high schools he himself attended while growing up in Omaha), with shots whose snowy-roofed buildings are framed by blank skies devoid of any detail. Amongst them are seventeen-year old students like Angus who swear unnecessarily about each other’s mothers but their introductions are tinged with nostalgia due to light folk guitar riffs played over scenes establishing every building and corridor.

Nevertheless, there is a quick and sudden departure from this style and music as soon as Giamatti’s Professor Paul Hunham is introduced; the expansive world and its gentle rhythms outside cut suddenly to his cramped quarters and the classical tunes he plays, as he mumbles to himself about the students he dislikes – which is to say, most of them. “Philistines,” whispers while smoking his pipe. His good eye swivels towards it at the sound of a knock on his door; Barton administrator Lydia (Carrie Preston) stands there with colorful Christmas cookies, which he grudgingly accepts without a word. He is an over-the-top version of an ill-natured scholar, who speaks rudely in every line that comes out of him and cannot have a dialogue without going around in circles about European antiquity since he thinks present-day reality is continuous with the past.

According to Payne’s portrayal of Barton Academy, it reminds one of how Wes Anderson saw Rushmore did though may be not quite with such a hyper-stylized aesthetic as Anderson. It seems like both were somewhere at some definite period yet nowhere all together due to gray sky shots behind snow-capped buildings minus details like if this school were dropped off in the middle of nowhere from Payne’s imagination (maybe sourced from multiple Omaha high schools where he was once a student). Teenagers such as Angus, who has foul language just like any other place infested by hormonal boys within proximity distance take verbal shots across each other’s mothers because they can but look back nostalgically through their introductions with light folksy guitar riffing scoring images of each building or hallway leading into them.

But then there’s that abrupt shift into both form and song when Professor Paul Hunham played by Giamatti appears. The next scene cuts sharply to his room where he has been looking out at country life only for us now to see him confined inside and playing classical tunes while murmuring criticisms about the students he despises. “Philistines,” he whispers as he puffs on his pipe. Then, all of a sudden, there is a knock at the door; and it’s Lydia (Carrie Preston), an administrator from Barton bringing him X-mas cookies with some weird colors, which takes them without saying thanks. A character like this must be familiar to anyone who has been around universities: a fictionalized grump who never utters anything that does not have sarcastic overtones while always veering off-topic in any conversation into his specialty (ancient Europe) since according to him, today’s world is just an extended version of what has already happened.

He also holds a grudge against the spoiled 1 percenters and legacy admissions that seem to make up most of Barton’s student body, which he shows through words and strict grades that could end all any boys’ college prospects. When Angus stands up to Hunham, the instructor slickly turns the other boys against him. But as winter break is about to prove, there’s more than that.

Four students will stay at school all month of December, an unfortunate situation for Hunham who has been picked out to watch over them – or rather give them another semester of work as he puts it himself. However, Angus becomes one of them when his mother cruelly comes up with an excuse why her son shouldn’t come home during Christmas in order to spend time with her new husband.

In the long run Angus alone remains within Barton’s walls after chance leaves him a holdover; therefore he spends two weeks with Hunham and Mary (Da’Vine Joy Randolph), the sharp tongued head cook of school who is grieving for her son lost in Vietnam War. The threat of being drafted looms large over Angus, as does a military academy being the only alternative if he gets kicked out of Barton – hence his impatient outbursts (and mutual contempt between himself and Hunham) feel fraught with immediate stakes.

The more they are forced into each other’s company – mostly eating in an empty dining hall yet sometimes lounging before the school’s only TV set –the closer they become like family albeit one that is disjointed and dysfunctional. From this Payne begins opening each character while zooming on their faces using gentle close-ups showing their confrontations towards each other as gateways towards their pasts and complete personalities. And as The Holdovers continues its 133 minutes length, it feels more like truly getting to know someone gradually such that one can understand some strange things about their personality without having to ask every time or think too much.

There is a fluidity to Payne’s scenes, and his characters’ dialogue crackles with a freshness that never seems clichéd thanks to Giamatti and Sessa who inhabit their roles completely, tone by tone. Giamatti waddles into each scene with his eyes wide open, like someone who keeps trying to say the right thing but ends up being offensive anyway; it is an enthralling portrayal built through conversation and contemplation. Conversely, Angus has a short temper and would rather have things Hunham can’t provide for him. Hunham can’t provide the right environment for Angus as he will be taking care of him over break term since he won’t be able to give him enough space to deal with family rejection issues. Secondly as a male authority figure incapable of looking beyond his own self and constrained by narrow academic guidelines he isn’t able to offer Angus the warmth and guidance that he so desperately needs from some father figure.

Perchance they are put through various comedy of errors including a trip to the emergency room at some point due to certain circumstances arising from Angus’ desire to break free from Hunham’s leash (and Barton’s coldness) where they come to recognize each other’s hidden weaknesses. Gradually, their fierce looks towards each other melt into expressions of familiarity. Their disdain changes into curiosity and finally affection but with Hunham’s over wordy history-talk clashing with Angus’ direct and sharp jibes it is highly entertaining bumpy road.

These exchanges should feel disjointed yet there is a quick-witted musicality about them that Payne achieves through his consistent concentration on ethos development and presentation. Giamatti and Sessa, in turn, translate this rhythm into body language and physical comedy – one scene in particular, at a liquor store, turns the duo simply walking around into a finessed two-man act – and when it comes time to focus this energy, they find laser-precise balance between their characters’ egotistical armor and the suppressed emotions it protects. And while Mary does occasionally feel swept into her own little corner of the film, let it not be said that Randolph doesn’t also swing for the fences by being often portrayed as an inconsolable voice of reason trying to make them see each other better as more well-rounded people like ego trying decide how much pompous super-ego and volatile id a person can have at once.

The more we get to know these characters; the more we learn about ourselves inside out–at least in ways that provide greater context for their drama–but also in terms of making all those cracks and retorts almost go without saying; you understand what your loved ones might say before they speak. Of course, this makes their punchlines no less funny. It actually feels like we’re being let in on one secret after another—those inside jokes where teasing your best friend or sibling’s insecurities is good natured. The Holdovers film, therefore, allows its comedy and drama not only to coexist but often intertwine in the same moments. Thus, it becomes funny and emotional at once as it reaches a climax that pulls heartstrings through melodrama but still appears cathartic in a realistic way by translating love into character-specific acts.

Verdict

The Holdovers is Alexander Payne’s most accomplished movie yet – a coming of age dramedy about an explosive student and his grouchy teacher. Dominic Sessa shines as the angst-ridden youth he plays while Paul Giamatti has never delivered such an inspired performance as a caricatured grouch with kinetic vulnerability.

Also, Read On Fmovies