Where would you go if you were lost, Can you find a way home? This is the path that filmmaker Scott Derrickson has selected in so many ways. Somehow, during pre-production of Marvel’s Doctor Strange In The Multiverse Of Madness (perhaps through an orange portal that glows) after directing the character on-screen in Doctor Strange in 2016, he finds himself back in Sinister territory with this horror film comeback. There are some very dark themes here; Ethan Hawke features prominently as do his regular co-writer C. Robert Cargill… and Jason Blum as the producer. So yes, Derrickson is home.

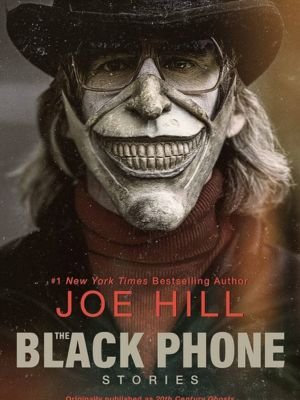

After his last flirtation with multi-million-dollar blockbuster movies, The Black Phone seems less like a step backward than a movie about looking back at what it really means to be at home; at Derrickson’s own background; and at forces (and friendships) that shape us into who we are. Joe Hill’s short story from his collection 20th Century Ghosts published in 2005 serves as the best prism through which these thoughts may be explored resulting in a bleakly premised adaptation whose personal demons converge into an unexpectedly warm hope-filled and – yes – frightening film.

The director has talked extensively about his own childhood concerning The Black Phone—having been raised up in violent ’70s Denver slums or something of the sort for him. It was not only during that time when parents physically disciplined their children and boys fought bloody backyard brawls but also when Ted Bundy (who murdered several people across Colorado around then) almost became a specter hanging over everyone’s heads’. The pressure of all these things revolves around Finney, played excellently by Mason Thames making his big screen debut in The Black Phone. He is almost thirteen years old growing up amidst violence filled ’70s Denver where he always sees signs of danger: his alcoholic father takes off his belt to flog him, he is constantly being ambushed by bullies lurking through the quiet corners and then there is the local folk tale of ‘The Grabber’ child catcher that adds to his constant fear of abduction. Before he was taken captive in The Grabber’s basement, Finney existed in a dangerous environment.

Derrickson’s film spends quite some time outside before enclosing its protagonist within harsh concrete walls — turning memories into movie scenes with Linklater-like precision. ’70s rock is blaring on the soundtrack (‘Free Ride’ by The Edgar Winter Group cannot help but evoke Dazed And Confused), bottle rockets are flying overhead, and kids are bragging about seeing The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in bathroom stalls. It all feels nostalgically recalled – but this warmth exists alongside forever looming physical and emotional suffering, stories of boys going missing with black balloons left at sites for their disappearance. In no way do these completely exclude each other as Derrickson captures both the nostalgia and brutishness without losing sight of one another.

Once The Grabber bundles Finney into his black van, the film dials in on its central conceit: that the killer’s former victims can speak to the boy from beyond the grave through a disconnected landline attached to the basement wall. It is here that The Black Phone plays like an Amblin movie in its darkest possible incarnation (darker than IT), with child ghosts calling up to help Finney escape a similar fate. Hawke, who has played a couple of villains this year apart from being Moon Knight, does an extremely terrifying and exciting physical performance when he swaps out the upper and lower parts of his devil-horned mask as if it is some fucked-up psychological exercise — changing frowns into snarls or malice-dripping Man Who Laughs grins; sometimes, he exposes his eyes or mouth entirely. Hawke becomes one with those masks, perfectly moulded to his facial contours. And it’s difficult to look away.

The Black Phone’s effective jolts and jump-scares should quell summer crowds looking for straight-up scarefests but it is dread that is most palpable — waiting for repercussive violence, whether in Finney trying to escape The Grabber’s basement or anticipating his father’s wrath. And salvation from all this lies in company; either through fellow kids’ lingering ghosts or psychic sister Gwen (Madeleine McGraw who also features as Gwen). She dreams in Super 8 (among other things) and quite possibly delivers the best cinematic prayer of 2022: “Jesus: What the fuck?!”

Though there are occasional tonal missteps — James Ransone’s brief supporting character Max embarking on his private investigation into The Grabber doesn’t sit right –whereas The Black Phone manages to be a mainstream genre movie that feels deeply personal and impassioned. It’s horror, delivered with considerable heart. Welcome home, Scott.

Also, Read On Fmovies