Mark Jenkin is a powerhouse filmmaker. Jenkins, a Cornish writer and director, has built since 2002 his style of experimental short films filmed in hand-cranked motion that culminated in the BAFTA winning feature of 2019 – Bait: an astonishing and black-and-white tale of gentrification tensions in a Cornish fishing village. This West country filmmaker played with film language but stayed firmly put within his region while coming up with something that looks like it was pasted from the past but is new (and he’s done again with his newest release).

His sophomore feature Enys Men (pronounced “Ennis Main” meaning “Stone Island” in Cornish) is a mesmerising follow-up which adds something to his already established signature style. Although Bait’s black-and-white aesthetic evoked early silent-era cinema, it had a contemporary setting (the influx of Airbnbs into Cornwall has been a topic for much grumbling); on the contrary, Enys Men takes place half a century ago but introduces Jenkin’s move into color photography, still shot via traditional methods using 16mm.

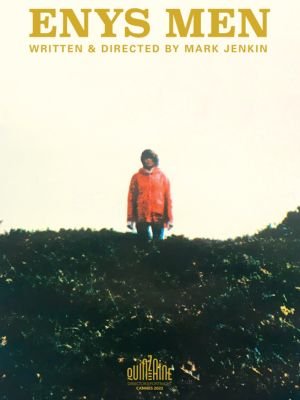

The transition from monochrome to colour is really pronounced here; its grade, grain and finish make certain colours stand out — most notably the bright-red rain-jacket worn by ‘Volunteer’ who remains unnamed throughout the film (Mary Woodvine). A visual motif reminiscent of Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (another psychological horror picture about grief and loneliness), whose release coincided with this film’s period of action.

It feels like 1973 in particular, yet also timeless, similar to Bait as well because of its lo-fi approach making it appear as if the entire movie were merely one lost reel among other found-footage washed ashore on some beach at Cornwall. The pacing is quiet and deliberate: every morning she comes out from her decrepit house on the tiny island off the coast, walks across to look at a cluster of what must be some rare wild flowers, takes soil temperature readings and enters them into her pencil-written log book. (This film’s response to “All work and no play…” is ‘No change,’ her daily update.)

As expected, any disturbance from that routine – played out again and again – carries with it an ominous undertone. (Nothing is more distressing than running short of tea supplies in this British horror movie.) With Jenkin’s trademark — strange static close-ups of motionless faces or disorientating cuts — there comes a new narrative experimentation when the metaphysical reality of the Volunteer blurs and things like milkmaids, singing schoolchildren and even the Volunteer herself start appearing for no good reason.

There are moments suggesting shared grief when a coastal community loses lives at sea, while between the flowers and the volunteer there is a paganistic link that allows ghosts from history to find expression in the present through their roots. However, this is never stated explicitly or given an entirely logical explanation. Enys Men belongs to the great tradition of English folk horror films which can be hard going; though you will feel as if something ancient has descended upon you whilst also being entirely new in Jenkin’s ambitious version.

Also, Read On Fmovies