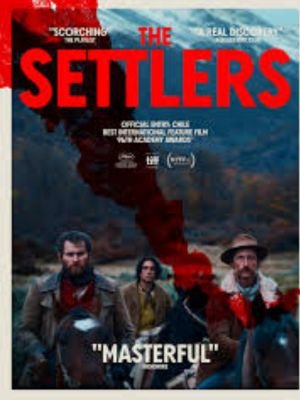

Even modern civilization has seen as deep a sin of colonialism as western. Frontier adventure stories that may sound cheerful are all situated in stolen homelands whose natives are unseen victims of a long-gone age. Killers of the Flower Moon turned subtext into text, an American crime opera about America’s first crime; its subject was how Americans systematically killed and exploited native people. Martin Scorsese’s movie premiered at Cannes two days before another Western came to the festival which makes explicit what is implicit of the genre: Chilean drama The Settlers is a spare and unsparing film based on another true story of genocide that would not be known by many from the history books.

There is already a hierarchy of oppression and violence at work here, with workers being dispatched like lame horses by foremen. As we will learn later on, life is cheap in 19th century Patagonia governed by real-life landowner José Menéndez (Alfredo Castro) who changed the face Argentina and Chile to suit his own greedy ends. There are three men he recruits to help him clear cattle passage through to Atlantic Ocean: MacLennan (Mark Stanley) – an ex-British soldier who probably had enough with Westeros heroics landing up in this unforgiving landscape that is no less fictional; Segundo (Camilo Arancibia), mestizo whose few words hides much talent for using firearms; Bill (Benjamin Westfall) – an American mercenary without conscience.

What can Englishman, American and Chilean find common ground over while treading across open prairies? People expecting some kind of camaraderie coming out these difficult experiences must have walked into the wrong movie because even amongst these wanderers they can’t decide whether horse is friend or food. Also their talk may have bitingly quick (“There are many things said about you, but I ain’t seen a damn thing yet”) snap but it never has the ring of amiability, or hostility that can grow to a begrudging respect. These men are separated by their differences and only united by how they can be useful to others with more power. The presence of various nationalities among them – which is ironically imitated in the movie being co-produced by eight different countries – underlines that colonialism was an infernally global project.

This South American country looks like it had been razed to the ground and then abandoned. When they meet on the beach a faction of outlaws under the command of a well-mannered old veteran (played menacingly polite by Sam Spruell, who has also played memorable villains this season on Fargo) it seems straight out of Mad Max. In describing their leaders, three ragged men try speaking in terms of every man’s land. Who gets to claim sovereignty over an entire territory? Atrocity and force are simple albeit harsh responses to this question. Initially presented as an exercise in cartography that turns overnight into something else, namely wiping out indigenous people completely before there is time for reflection; therefore, from this perspective, the film could be called post-apocalyptic because there would have been new world born upon burying another one in ashes and blood.

It is in his first feature film that the script writer and director Felipe Gálvez Haberle had a taste of mythic spaghetti western flourishes – the awe-inspiring vistas, nicknames written in letters larger than canyons and bewitching soundtracks – only to keep itself away from indulging into pulp coolness characteristic of this genre. The violence does not have any fun factor yet there is a time for us to relish it even when staged with muscle; a bunch of desperate cowards sneaking around with cocked rifles through a dense fog is the closest we get to action scene. Dissipating some of his casts for English-speaking viewers who are used to calculating the general spatial arrangements of their heroes within their minds, Haberle managed to use these conventions most effectively revealing the horror of manifest destiny. Even his apparent protagonist, Segundo, an iconically reticent figure, becomes neither more nor less than an accomplice or greedy collaborator weighed down by conscience but refusing to condemn looting and ravaging.

Bearing witness as a purpose, incidentally, makes The Settlers Chile’s official submission for this year’s Best International Feature Film Oscar. Hence its exclusion from the shortlist: It is closer to brutal Aussie oaters like The Nightingale than any tale about how America was won with its quick ugly killing and its massacres and sexual assaults. A dark underbelly of Chile’s history is laid out by Haberle whose country has never really discussed one shameful chapter until now: the Onas’ genocide in Tierra del Fuego archipelago. In fact, there is real integrity in de-glorifying Westerns methodically…except that this results in films that operate between two extremes alone: meditative silence alternating with deadening mercilessness.

At least until Act III. With a talky oddly expressed closing passage and leap forward through time The Settlers stakes new ground. It’s clear that this is not just a play about the terribleness of what was left unsaid for the sake of national identity; it is also an illustration of why such atrocities are forgotten, often with the aid of well-meaning crusaders whose main concerns are their self-images rather than telling truths. And like Scorsese, Haberle is clever enough to scrutinize his own supposed greatness as well as think over who can narrate these kinds of stories, for whom and why. That is what really makes his Western revisionist: it knows that even efforts to make amends for past wrongs have been authored by victors.

Conclusion

Felipe Gálvez Haberle directed this first feature film from Chile which is a chilling tale about colonization and genocide featuring three bruised men making their way through places in South America that had been claimed by their rich boss. There’s little doubt that while this Cannes awarded motion picture borrows some grandeur from spaghetti westerns, it hardly seeks thrills or drama in a conventional sense. Nonetheless, its cruelty has integrity, and there is a clever idea behind its final act’s trickery. If nothing else, could be said to go well with Martin Scorsese’s much longer but likewise themed Killers of the Flower Moon although this double bill would likely break most people’s spirits.

Read The Settlers on Fmovies

Also, Read: