“Do you just think that you can act without consequences?” she asked him one evening, as the threads of their life began to fray. It is a query that sounds throughout not only their home improvement project but also the very soul of their shattered lives. The couple-to-be desires to announce themselves on HGTV with an original show based on their “holistic” home philosophy and “passive living” perspective featuring a slimy producer (Benny Safdie) with skeletons in his closet. They’d deny it – then invent a counter-argument that seems helpful for Native Americans and Hispanics in the neighborhood against it – but they are gentrifiers, who want to turn the small impoverished town of Española, New Mexico into an eco-friendly hotspot.

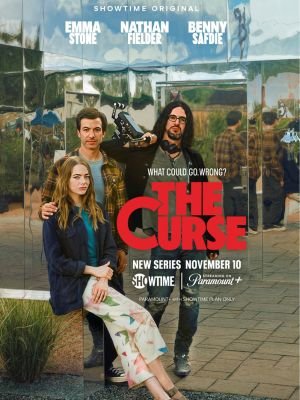

However, things start going upside down – and I really mean upside down – when Asher, through every fault of his own, is “cursed” by a young girl in the parking lot of the local supermarket. Thus was born The Curse by Fielder and Safdie, an amazingly wacky movie despite being punishingly uncomfortable, it was also about colonization and greed.

Supported by excellent writing, directing, and acting The Curse has its entire hand on the pulse. This show’s behind-the-scenes production decisions are made amongst plenty of other reasons that make this series’ tone so confusing and almost mystic. Whitney and Asher remain under surveillance from The Curse’s cinematography rather than them becoming subjects themselves. Apart from nonstop coverage by reality TV camera lens with all its enhanced definitions we normally see them framed therein; once again there is always another space beckoning beyond windowsills or corners where they cannot be seen, always lurking somewhere afar off so much as they were unwanted company inside waiting for wings where they never saw anyone but felt like someone watched constantly over them or something did at least apparently every day every one* else’s existence even if they seemed oblivious of this. And so on, in whichever way they would like to interpret these details because their motives are all out in the open, whether they know it or not, and we see that both sides remain right to us.

White viewers may see some of themselves there, too – if they’re willing to admit it – and yet keep coming back week after week because of the show’s comedic-yet-tense edge. The cast is all firing on all cylinders working together towards a single message while embracing Fielder’s signature cringe comedy. It is satire with well-woven characters as their performances offer more than meets the eye submerging them into moral greyness.

Whitney Stone is a tornado of irrationality complicated beyond measure by her need for control. Although she has played up her role with warmth, sometimes she can be even more entertaining when she reveals herself through her activism façade* because everything here hangs in guilt only when one peels off its layers of pretentiousness. It’s equally an addiction to being “a good person” and comprehension of actualities around meanness that have made Whitney enter such a sphere where she lives today…. In any case, Stone’s excellent performance was full of tiny acts of kindness signifying nothing much but still indicating how well Whitney could play along despite having an illusion that she does what is right and decent during whatever moment each day*. Her existence just knows no better than happy ignorance which does not know anything concerning the outside world; this is how amazing writing works as superbly two-faced as acting done by stone in this part as well.

Then there is her spouse. Asher shows us who he is behind the closed doors and it’s obvious he won’t get his conscience in touch until it’s too late. Fielder’s depiction presents an emotionally flat, rational Asher—someone who always prioritizes these ideas rather than real sympathy by Fielder’s portrayal of him. All the while, his character thinks of himself as a friend to the communities he harms. It depicts him as someone who feels superior when he really isn’t.

Inevitably this reality of Asher’s true nature will hit him very hard, marking moments that show Fielder can act. It is his biggest appearance in a scripted TV series to date and he eats it up like a famine-stricken wretch but also manages to effortlessly connect with the nuances of his character’s twisted psyche. In Whitney, Safdie tells Dougie “You wouldn’t do anything good if I didn’t force you to.” Also before that point, he had asked Asher “Aren’t you tired of cosplaying as a good man?” by Whitney before she tells herself this same thing, Fielder makes Asher into everything abhorrent about humanity yet still somehow captivatingly repulsive; walking the line between one-toned morality and another. A performance that is wickedly deranged and devastatingly human in all its countless injustices.

Dougie played by Safdie with a sense of delusional duplicity, fits perfectly into the third spoke on The Curse’s strange triad with its show-within-a-show (Safdie has made some notorious A24 films with his brother Josh). Dougie has glimpses where war rages inside him thus projecting himself as a doomed and awful being but also dark ones where we see tears run down his cheeks onscreen indicating that there really are some nice things hidden somewhere deep within him.…..

Equally vital to the series’ dynamic is Nala (Hikmah Warsame), the young girl who curses Asher. Her unaffected performance is what helps make the central conflict work, and provides a strong base of both childlike confidence and insecurity. When Whitney and Asher’s Picurís and Tiwa Pueblo artist friend Cara Nizhonniya Luxi Austin, an actual Santa Fe artist fearlessly projects a contempt and revulsion, that also makes her one of the most impressive newcomers in any film this year; each frame she inhabits becoming a gloriously watchable testament to fear and righteous anger towards people who refuse to acknowledge Native experience (especially that lived by those indigenous to Española).

Ultimately, a higher power – is it? – has targeted the central couple for punishment. The Curse has an extremely malevolent tone, which grounds it in cosmic astoundings and strange happenings and John Medeski’s foreboding, ominous score on top of everything else adds to this vibe cake. It combines elements of electronic music that underpin Safdies’ film work (Uncut Gems and Good Time composer Daniel Lopatin serves as music producer here) with soundtrack cuts spotlighting musicians from marginalized communities. Alice Coltrane’s “Jai Ramachandra” acts as some kind of theme song for the program hence it captures the struggle to make a yearning cry of liberation recognized while accessing unknowns that lie beneath its surface. At times its appearance is scary.

From its opening scene to its last minutes, everything about The Curse is an image – every calculated move between Asher and Whitney. Are the Siegels only acting out their life for cameras even when they give away free rent and do native land acknowledgments? If you refuse to acknowledge what your mere presence does to people who have been here before you were born, that means The Curse says you are not exempt from being watched either. (Thus Whitney and Asher’s plan becomes or always was the real curse.) It makes us think hard, question decisions made, and seek underlying meanings until cameras go off; it is a thought-provoking series with layers after layers. Which frankly deserves more conversation than we can entertain in this review.

Also, Read On Fmovies