Kyle Edward Ball’s Skinamarink, unlike other horror movies seen in indie and arthouse theatres for a long time, could be deemed as an experiment that is lesser than the sum of its parts. This enclosed Canadian production is quite avant-garde in terms of storytelling; it centers on young kids who are left alone by themselves inside a dark house from where they cannot get out. The movie sometimes converts this creepy set up into a terrifying experience due to its visuals, which mimic the feel of an old film camera that was left unattended for hours without being turned off; even its point-of-view shots resemble “found footage.” It is however flawed when it comes to losing its tension through cheap startles and jump scares – a rather common trope in modern films.

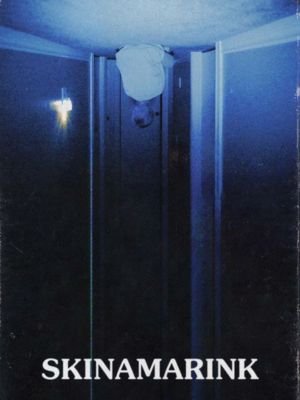

Ball, who also edited the film, runs the YouTube channel Bitesized Nightmares, which makes all his love for strange stuff (and creepypasta transformed into reality) visible in his first movie. The presence of some deeper global works about unsettling internet horror such as Jane Schoenbrun’s We’re All Going to the World’s Fair means that Skinamarink can be easily placed near them because both filmmakers drink from this same well. However, here Ball contextualizes this particular lens against a pre-internet era setting. It is 1995 and Kevin (Lucas Paul) & Kaylee (Dali Rose Tetreault) – cute kids whose faces we almost never see but their voices sound innocent and lovely — wake up at night in their two-storey suburban house that has neither doors nor windows as if they have vanished while their divorced dad disappeared without trace too. Much of the hour-and-40-minute runtime is lit primarily by the flashing lights of the CRT television set they stay up late to watch, and it casts flickering shadows across their living room walls and the toys scattered on the floor as the light trails off into darkness.

These spots in the dark serve as Ball’s canvas, through which he gazes at the unknown and invisible for extended periods, with a digitally reproduced grain further adding to the blurriness. Although it is clearly added in post-production (it was recorded digitally anyway), its recurring patterns and even slight alterations make it difficult to tell how much time has gone by.

This disorienting effect is intensified by applying some indirect angles that Ball and his cinematographer Jamie McRae strive to take in order to achieve not only obscurity but also place focus on their feet dangling from the sofa, old public-domain cartoons of mid-twentieth century they are watching or LEGO blocks and dolls moving without touch (even gravity is unreliable). Meanwhile, there is an unseen presence talking to Kevin and Kaylee by whispering into their ears what remains unintelligible via the microphone yet subtitled for audiences: such subliminal mutterings allow watchers understand them while still preserving their low-budget horror atmosphere. It feels real scary like you’ve just come across some sort of a wrong artifact that should never have been seen.

The name Skinamarink is borrowed from a nursery rhyme, an appropriation that effectively perverts a childhood memory, and the film as a whole carries this theme. In its most terrifying moments, the camera stays focused on what’s in dark closets and under beds, with no relief for children; no one tells them that there is not actually any lurking monster waiting to attack.

As such, Ball often paints a chilling picture of a family who has no protection against its own home. Whatever is really there – some ghoul or demon perhaps – soon becomes a chilling metaphor for loveless families and homes where pain reigns supreme despite bearing all the colorful trappings and store-bought symbols of child care.

No matter how successful each of these concepts may be on its own, Skinnamarink doesn’t do enough to connect them together in terms that resonate with its visual style. Though Chantal Akerman’s Hotel Monterey (1972) appears to be Ball’s biggest influence (a work mostly constructed from hotel hallways), his use of long takes that mesmerize the viewer also struggles with some overeagerness. While shocking sound stings and disturbing images may momentarily jolt us (as they would in “slasher” or “haunted house” movies), it further disrupts what holds Skinnamarink together by relying on more traditional horror scares.

Nonetheless, this movie requires patience but rarely delivers chills that raise your hackles as it forces you to confront distortions of the nostalgic and familiar. Instead, it expels us from its little world that it has strived so hard to make real only annoyingly upsetting itself in turn. This could have been hair-raising ending up as lame instead.

However, considering that one would find an indie movie costing $15k playing at 600 North American theaters is simply mind-boggling. Movies like Skinamarink hardly come across mainstream audiences.. So even with its stylistic imperfections, it is a positive addition to the health and diversity of theatrical exhibition – less for Skinnamarink itself than for what it could portend about a coming crop of imaginative web-bred horror indies or Ball’s future in filmmaking.

Verdict

Skinamarink is a creeping experimental indie that stands out from most mainstream horror films because it insists on remaining silent and dark for too long. It digitally imitates celluloid, its plot –two young brothers trapped alone in their house without any escape– distorts familiar domestic objects in elusive and nightmarish ways, making this film different at least if not always successful.

Also, Read On Fmovies