Alfonso Cuarón is undoubtedly one of the greatest filmmakers of his time. And Roma his new masterpiece that will become a classic, albeit not one that will instantly excite the crowds. It’s an exceptional and original film, and for the first time I felt the urge to keep my favorite director as far away as possible from the usual Hollywood commissions like Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban or Great Expectations. He really feels sorry for you. It’s much better if he reappears five years later with another uncompromising vision that no one else would have made.

It is understandably funny that while Trump called Mexico the source of the most disgusting poo and decided to build a wall, Hollywood was ruled by the Oscars (and shaped its face today) by Cuarón, his companion Alejandro González Iñárritu, cameraman Emmanuel Lubezki or Coco. At the same time, several times over the past few years, we have produced another important work with Mexican blood – and this time really earthy, without colorful celebrations of the local culture and folklore. But the political dimension is perhaps the least interesting thing about Roma, because it is a fragile author’s confession, elevated from some nostalgic-narcissistic recollection to a timeless reflection on the pitfalls of life.

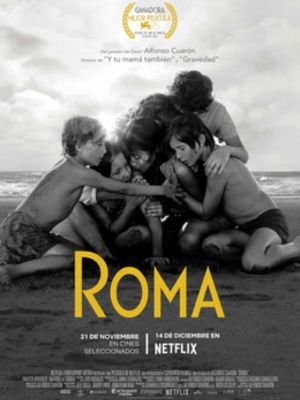

Roma: PHOTO GALLERY

In its center are two maids, a mother and a grandmother, revolving around four children in a villa in the seventies. After all, this is why the film can easily be understood as a statement about the fate of women. But I wouldn’t see any sharp feminist perspective in it – quite possibly it’s a coincidence and simply a result of the fact that in Cuarón’s childhood, the boys around him didn’t work very well. But it’s not that important, because the struggle of those women against adverse circumstances is not shown in any way spectacularly… and that’s what makes it even more powerful.

It’s laughable to see how much effort goes into making the film look as ordinary as possible. Complex scenes are orchestrated to capture the mundanity with which the maid Cleo vibrates during her working day, without poetic ballast, but with a precise feeling for the daily routine. How it works within the microcosm of one large family, which also doesn’t have it easy, and how it tries to cope with its sudden unpleasant situation.

Cuarón imprinted a very strict formal concept on the film, which he shot and edited himself this time (after all, it’s hard to imagine that his court cameraman Lubezki would suddenly let himself be laced like this). At first, it is perhaps too non-viewerly and unkind, as most of the movement takes place in the depth of the shot, perpendicular to the camera, the viewer may have more distance than they would like.

Even the gradual mapping of the apartment from right to left and back again (the best ad for the Panorama function on the iPhone? 🙂 is not engaging by any means, but when you add to it classically Cuarón driving and, on the contrary, static shots from privacy, it stands out how perfect the visual system Cuarón has imprinted on the film and how precisely he can hold it, and at the same time, it will eventually be filled with real emotions and existential pains and joys.

It is an extremely plastic capture of its time, its environment, its ordinary heroes. Cuarón’s virtuosity can certainly be seen in the details: From the coldness of the pivotal scene in the hospital, from the cleansing finale, from one shot that so perfectly manages to capture the beauty and fleetingness of love over time against the background of a foreign wedding, from that truly magical passage with a local celebrity standing on one leg (by the way, one of the few moments where you can really draw the parallels with Fellini and the Italian inspirers), but also, for example, from the New Year’s Eve muttering, shot from the perspective and height of children’s eyes (and the eyes of a kneeling maid).

Nevertheless, Roma is a really compact and in many ways heartbreaking drama, which manages to reflect life with all its shit in an unprecedentedly vivid and captivating form.

It is a film that touches on motherhood, family and love in many meanings and forms. At the same time, it is truly exceptional in contemplating whether life has meaning even after great shocks and trials, strong in the unpretentious finding of hope and the literal usefulness of a person even on the edge of his existential bottom (and not in the dull, old-fashioned sense of the word that “we struggle, therefore we are”, but much deeper). These are not easy topics, and Cuarón does not present them in an easy-to-read package, so I’m a little afraid that especially younger viewers, under thirty, without children and with balls, won’t be so moved by the film. But I find his reminiscences of his youth and the essential women in his life even more impressive than when giants like Fellini or Bergman delved into similar waters.

I don’t know how much the film’s subliminal optimism can be shared. But I’m definitely sure that movies like Roma make life more bearable and meaningful.

Also, Read On Fmovies