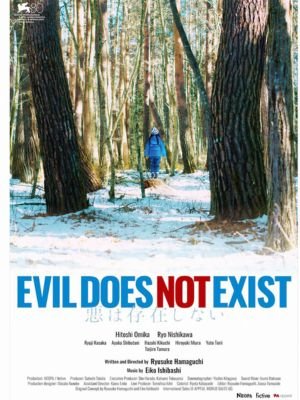

In the past, Hamaguchi Ryusuke’s film Drive My Car was awarded an Oscar; inspired by Chekhov, these scenes of dialogue were lengthy; and there were so many long pauses that drew people in like a magnet. It is for this reason that his concentration on still life with reflection has turned him into one of the most interesting dramatists in modern cinema. He continues to employ the same approach even when it comes to nature itself for better or worse in his recent movie Aku wa sonzai shinai (or Evil Does Not Exist). However, it takes quite some time until we see it turn into another riveting humanist drama by Hamaguchi.

At the beginning credits which are extended while looking at nature’s beauty through one eye, Hamaguchi presents us with snow-covered trees and frozen rivers found around Mizubiki Village which is about two hours away from Tokyo. On ending the winter season, silent Takumi (Omika Hitoshi), who works as a general laborer, still performs his everyday duties: fetching water for the villagers from a local mountain stream and chopping logs to fuel their stoves. While engrossed in this activity he forgets to pick up Hana (Nishikawa Ryo), his 8-year-old daughter from school again but that is because everybody knows each other in such a small village where she can find her way through forest trails.

Mizubiki feels like a community and looks calm albeit with occasional subtle deviations from conventional cinema that are introduced by cinematographer Kitagawa Yoshio together with Hamguchi such as characters walking out of frame behind trees or mounds and shooting footage with reduced shutter angle which results in jitters common during action scenes due to motion blur reduction. In contrast to surroundings full of purity, there is something awry about them suggesting imminent danger. Subsequently, a local talent agency sends its representatives to consult with the residents on the possibility of building a luxury glamping site that would have an impact on surrounding areas—something Takumi is surely passionate about. In this kind of conversation, Hamaguchi’s films excel, giving a character through conversational rhythm.

Even though it takes some time before the film gets here and leaves behind the countryside; there is now an atmosphere of grim humor. The impoverished villagers are worried about what negative changes may happen downstream as a result of the extravagant center – meaning real trickle-down economics – but even though they discuss these concerns with various camping site officials, these guys never really hear them out properly. As much fun as it can be to see them inadvertently poke holes in their developed plans, there is also an element of helplessness in the objections from locals because they are already defeated.

However, rather than advancing towards this finale right away, this movie takes its time by focusing on those agents themselves first as part of a larger machinery based in Tokyo that comprises people who are morally guilty but not legally culpable for their actions. It is to his credit (as well as his ethical stance) that practically all characters here seem to illustrate such an approach irrespective of how deeply they are engaged in this scheme: something which can also be seen as optimistic even if their fickle nature remains prevalent when envoys come back home and go looking for directions by asking Takumi to tell them more about Mizubiki Village.

Evil Does Not Exist is a film about community, dignity, and what people owe each other, notions that are thrown into disarray when the ruthlessness of modern industry gets involved. Moreover, even as these images attempt to mimic nature in a way that Hamaguchi Ryusuke intended, they come across as unwelcoming and disagreeable with his past works. On the other hand, they capture the villagers and their surroundings at once while at the same time signifying all these forces that victimize them for no reason despite their innocence. In Hamaguchi’s view “evil” may not exist but apathy does exist and looking at the end result there might be very little difference.

If it often feels like Evil Does Not Exist is stuck in limbo – if its shots of nature seem to belong to a different aesthetic altogether yet retain some importance in terms of plot – then this is because it is actually a spin-off from another movie. He has previously created other material based on this footage mainly consisting of dialogue scenes as opposed to Gift which will have no words at all until its world premiere during Belgium’s Film Festival Ghent in October.

Hence, this is why most of the long conversations play out like epicenter of the film leaving so many transitional shots of nature feeling redundant. However, as well as working here for Gift we get hints about section from him too which could also be viewed as a likely powerful alternative version. His silent observations on human exertion are just as worthy as his group discussions.

It didn’t help that he made such dramatic landscape interventions indifferent; it was only the human eye that could bring them life through flowery language to evoke emotions. Though depressing when filtered through Hamaguchi’s dramatic lens; when his characters commune with nature even silently, it can be quite haunting.

VERDICT

There is an earnest change in style from him that does not however accomplish its goal of meditating on nature in Evil Does Not Exist. On the other hand, his best moments amount to yet another fascinating melodrama from the being whose forte lies in observing people rather than their natural habitats.

Also, Read On Fmovies