Benjamin Millepied’s first full-length feature, Carmen, a musical romance set in a desert, is an unremarkable movie which is even more disappointing when compared to the opulence of its source material. It was loosely adapted from Georges Bizet’s opera Carmen that was composed in 1875 – you might be familiar with this work because it has a famous solo called “Habanera/L’amour est un oiseau rebelle” that anyone can recognize even if they have never seen its performance. However, the film itself bears little resemblance to the play. The fact that it totally ignores almost all elements of Bizet’s composition is not the issue; what becomes problematic is that Miliepied and co-script writers Alexander Dinelaris Jr., Loic Barrere don’t substitute the original’s essential elements with anything new or innovative.

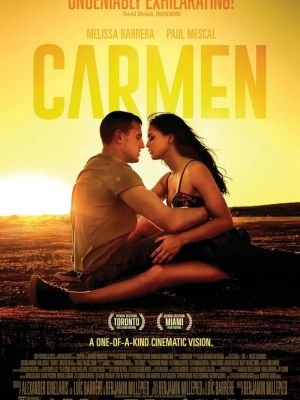

The filmmakers relocated the initial story – about a soldier who falls for a brave gypsy woman in Spain during 1820s – to the US southern border where young Mexican girl, Carmen (Melissa Barrera) runs away from her violent home town and gets into America where she becomes involved with an ex-US marine Aidan (Paul Mescal). While a new premise opens up scope for political reflection in contemporary society as put across by its tough dusty landscape and scorching visual tone, it remains superficial and does little to impact gut-level reactions of characters.

Similarly effective tonally is how terrifying gunfighting occurs with bullets tearing through night air before both flee away like lawbreakers eluding arrest together reminiscent of modern-day Bonnie and Clyde except minus their glamour or moral complications. Thereafter several minor musical interludes occur one at each turn more fluid and dreamlike than previous ones though these rarely impact either the character nor storyline at hand although often providing some sightly scenes.

While these encounters are presented stylishly, they also betray Millepied’s lack of commitment to the adaptation. Its musical aspect is merely in name; the whole movie contains just a few scenes of abstract dancing, which rarely turns into singing and consequently leaves very little room for genuine emotions. The movie interrupts its story so that performers can re-enact previous story elements as interpretive dance but without using movement to fully convey who they are or what traumas they face on their journey. However, even then if these characters had the privilege of expressing themselves through song, it would be difficult to picture how any of them could have left an impact despite each actor’s track record (Barrera in In The Heights: The Musical, and Mescal in his after sun (Oscar nominee) performance).

To a large extent, the lead couple is so simple that it becomes almost inactive. Carmen, who does not have any background in trauma and mostly suspects Aidan for a stranger she will surely make love with when their destination draws close yet the journey hardly entails it. Nevertheless, before he meets Carmen, we see some dimension to Aidan through his PTSD reference and general pursuit of purpose. However, once both characters embark on their journey together, tragedy is cast aside to allow room for a monotonous “will-they-won’t-they” kind of romance which could exist alongside the tragic and poetically inform each other on intricate ways. Why do they dance them if that is not the withheld anguish that they desperately want to show?

If the actors are wasted, then even more waste occurs with the composer. Nicholas Britell is a generational genius when it comes to music for movies like Moonlight and If Beale Street Could Talk, as well as shows such as The Underground Railroad, Andor, or Succession among others but his score here has rarely found an imagery to accentuate with recurring themes or ideas worth investigating via melodies. At least Millepied’s camera (with cinematographer Jörg Widmer) is able to capture the vastness of the desert landscape making it perilous But once he looks at the human body or face his lens loses its perspective in terms of physicality or emotions.

The movie does have moments of raw operatic expression but they are few and far between being totally irrelevant to Carmen and Aidan that one starts wondering whether these two leading duos belong to another film (like maybe a realistic work by someone able to magnify their understated emotions). In this first scene, a woman dances defiantly against certain death, however, from this point onwards movement and musicality do not pass onto Carmen.

Another scene includes US border patrol agents joined by civilian militias – part of a chain of events that leads to Carmen and Aidan meeting – which almost captures the wretched aggression that might theoretically drive a story about a migrant woman running from race hate and blood-lust. Nonetheless, despite Aidan getting reluctantly embroiled with these people, he is portrayed as pure-hearted and straightforward; there are just external barriers to their love affair, which exist mainly off-screen.

One redeeming factor for the actors would be Rossy De Palma’s enigmatic nightclub owner Masilda who is only a minor character where the couple seeks refuge. In her dialogue, she brings out some sense of motherhood in the Spanish actress who has limited screen time but evolves into a wise old lady when she takes on her musical interludes alone. The twinkle in her eye is magical because it represents an idea that Carmen could have been a movie where love and pain can find a brief yet deep expression through dance. Unfortunately, this never happens.

Verdict

Carmen, whenever any semblance of dream abstraction emerges, immediately resorts to its usual formlessness that resembles a desert without heat in a romance about two faceless individuals escaping from danger. It is not mysterious and it is not loud either. This is one of the most mystifying musicals ever – in other words, by far too much a musical for an immersive seductive realism yet just not enough of a musical to be passionate at all.

Also, Read On Fmovies